Disclosing an Interest in a Foreign Account

by Gregory S. Dowell

The IRS has long had a requirement for a taxpayer to disclose his or her interest in a foreign bank account. While penalties were built into the Tax Code to enforce this disclosure requirement, the IRS was often lax about enforcing the provisions or the penalties. That laissez-faire approach has changed in recent years in a very, very big way.

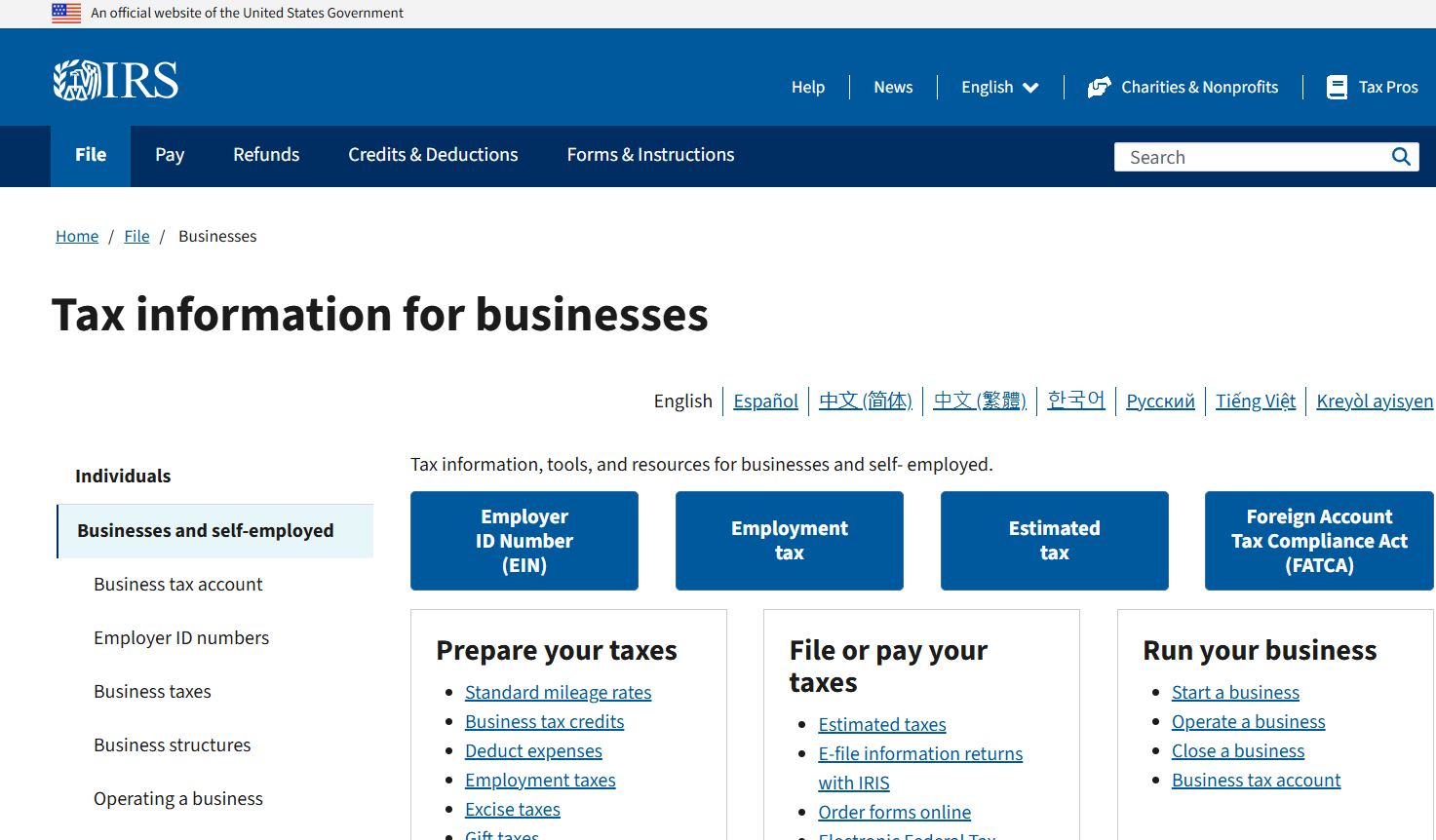

The basic law requires that a taxpayer must inform the IRS annually if the taxpayer has an interest in or signature authority over certain foreign accounts. The taxpayer does this in the following ways:

- Check the box in part III, line 7a on Schedule B of the taxpayer’s individual income tax return.

- If necessary, attach form 8938 to the annual tax return, if the account balances and the value of other foreign financial assets total more than $50,000 on the last day of the year or more than $75,000 at any time during the year (for single filing status; for married status, the amounts are $100,000 and $150,000, respectively).

- Taxpayers with account balances in foreign accounts that in the aggregate exceed $10,000 during the calendar year must also file form 114 (formerly form 90-22.1) with the Treasury Department by June 30th.

If a taxpayer is required to disclose, failure to disclose the existence of foreign accounts can lead to perjury charges and the existence of undisclosed offshore accounts can lead to charges of tax fraud. In the past, many taxpayers have relied upon the belief that the IRS was powerless to discover the existence of foreign accounts. Recent IRS victories in court, however, have poked permanent holes in those beliefs. For example, in addition to paying huge fines, international banking giant UBS in Switzerland was forced to turn over the names of more than 4,000 U.S. taxpayers with hidden Swiss bank accounts. A recent agreement between the governments of Switzerland and the U.S. will result in more banks turning over the names of U.S. citizens who maintain their bank accounts abroad.

Of course, the issue is not just one of disclosure, but of failure to pay tax on the foreign income. The basic concept of U.S. income taxation is that U.S. citizens are taxed on their worldwide income, regardless of where that income originates. If all taxpayers reported and paid tax on their foreign income, the IRS’ concern over the additional disclosures on forms 8938 and 114 would probably be less heightened. The reality, as the IRS has proven, is that much of the income earned on those foreign accounts has not been reported and taxed for U.S. purposes.

To encourage disclosure, the IRS has developed a disclosure program, dubbed the “Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Initiative” (“OVDI”). As of December 31, 2012, the IRS has collected some $5.5 billion in taxes, penalties, and interest from this program, from some 39,000 U.S. taxpayers.

Some taxpayers will always choose to roll the dice and continue the pattern of noncompliance, hoping they will not get caught. However, if a taxpayer historically has had foreign accounts that have not been disclosed to the IRS, there are only two possible approaches to consider:

- Choose to disclose under the OVDI program. Doing so will result in taxes, penalties (albeit at a slightly lower level), and interest for up to 8 years, but will avoid the possibility of criminal prosecution.

- Begin disclosure of foreign accounts immediately, and consider amending returns for all open years. This approach might best be considered when the taxpayer has reported all of the income from the foreign accounts on their tax returns and has paid the appropriate amount of income taxes.

The approach that fits each situation best will depend on the particular facts and circumstances in each case, as well as the risk tolerance of the taxpayer. Existence of willful or reckless behavior by the taxpayer may be good reason to consider the OVDI program. It should also be taken into consideration that the IRS will likely not allow a taxpayer to enter into the OVDI if the IRS discovers the non-reporting on its own and initiates the compliance process.

What taxpayers should absolutely count on is the IRS’ continued emphasis in this area. Too much time and money have already been invested by the U.S. Treasury, and victories for the IRS are starting to pile up. Taxpayers with undisclosed foreign accounts should assume that it is likely that the IRS will eventually discover these accounts. Doing nothing and ignoring the problem will not be a good option.