Foreign Accounts: Take the FBAR Requirements Seriously

By Gregory S. Dowell

June 25, 2019

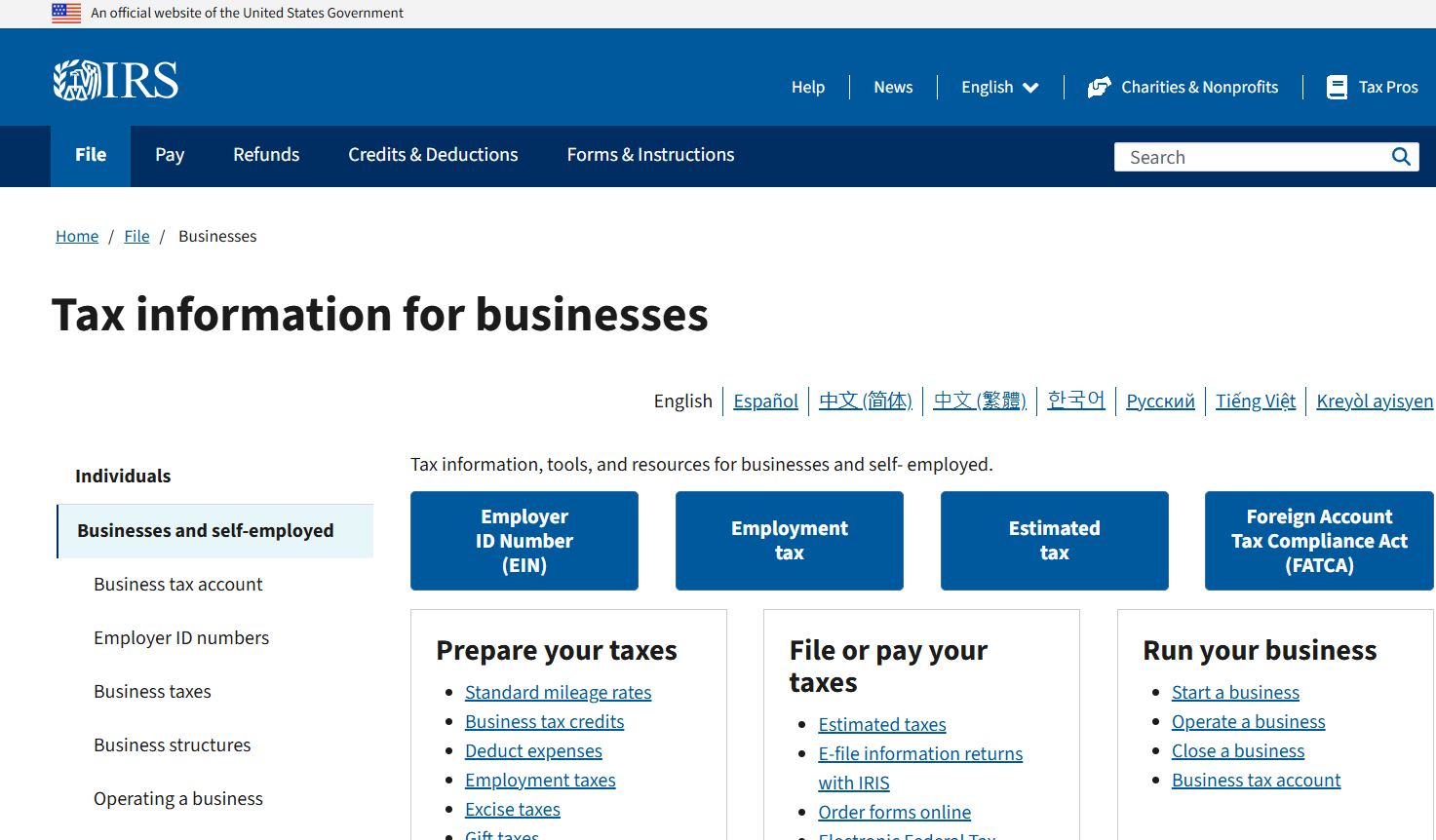

When taxpayers have foreign assets (bank and brokerage accounts, real estate, collectibles), they are required to file foreign financial reporting forms on an annual basis. Filing is required when the value of the assets is equal to or greater than $10,000 at any time during the year. The filing is made on form FinCEN 114, which is more commonly referred to as the FBAR form. The filing requirements have existed for several years now, and there are significant penalties for failing to file the form. The penalty for failure to timely file an FBAR varies according to the level of the taxpayer’s culpability. A willful violation can result in a civil penalty of up to 50% of the balance of each foreign account or $100,000, whichever is greater. A claim by the Government to collect civil penalties for a willful violation consists of seven elements: (1) the defendant was a U.S. citizen at the time of the filing; (2) the defendant had a financial interest in or signatory authority over the account at issue; (3) the account balance exceeded $10,000; (4) the account was in a foreign country; (5) the defendant failed to disclose the account; (6) the failure was willful; and (7) the amount of the proposed penalty is proper. In the past, when these filing requirements were newer and were being emphasized, the IRS has been very willing to accept late-filed FBAR returns in many circumstances, as a way to gain voluntary compliance.

Taxpayers, however, would be wise to heed the findings of the US District court that held that a US citizen willfully failed to file FBARs regarding his Swiss bank accounts. In a recent case, the court found that the taxpayer’s testimony was not credible; he was financially sophisticated and had created financial structures to evade taxes.

Some background: Edward Flume was a US citizen and an experienced businessman who lived and worked in Mexico. As his foreign holdings grew, Flume used a Mexican tax preparation firm, and incorporated his business in the Bahamas initially, and then reincorporated it in Belize. Flume also opened a Swiss account under the corporation’s name with UBS in 2005; only his wife and he had signature authority and they held all of the stock. Flume signed a waiver of a right to invest in US securities, which the IRS later said was evidence that they wanted to hide the activity from US authorities. Flume failed to report his interest in the foreign UBS account to the IRS in 2007 and 2008, in accordance with the FBAR filing requirements, although he did report the interest income on a Mexican bank account. Separately, UBS was under investigation by the IRS on a charge of a broad tax-evasion scheme it was conducting for its US clients. Upon learning of the investigation by the IRS into UBS, Flume moved his account, first to another Mexican bank account, and then back to the US. Finally, in 2010 UBS agreed to comply with the IRS and released the names of its American clients, including Flume.

In June of 2010, Flume filed the delinquent FBAR tax returns for 2006 through 2009, although the value of the accounts he reported were significantly understated. Even though he was eligible, Flume did not apply to the IRS’s Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Initiative (OVDI), which might have reduced his liability if he had disclosed the Swiss bank account. In 2014, the IRS determined that Flume had made a willful attempt to avoid US taxes and assessed penalties in excess of $450,000. Flume claimed the failures were inadvertent, as he had no knowledge of the FBAR requirement until 2010.

The District Court concluded that Flume’s 2007 and 2008 FBAR filing failures were willful, noting the following reasons:

- Flume’s testimony was not credible and contained numerous contradictions.

- Flume changed his account of when and how he first learned of the FBAR reporting requirement at least twice.

- Flume’s account of the discrepancies between his delinquent FBARs and the actual balance of his UBS account strained credulity.

- Particularly when viewed in light of his disingenuous testimony, Flume’s financial structure reflected a sophisticated tax-evasion scheme.

- Flume’s testimony about the 2001 transfer of Wilshire Holdings, Inc. from the Bahamas to Belize further demonstrated his familiarity with international tax laws.

- Flume’s tax preparer’s testimony that Flume was sent an annual reminder of the foreign-account reporting requirements was credible.

- The fact that Flume disclosed his Mexican account on Schedule B of his tax returns suggests that he was aware of the foreign-account reporting requirement and made a conscious choice not to disclose his Swiss account.

- Together, UBS’s client-contact records and Flume’s trial testimony establish that Flume was aware of the IRS investigation into UBS by mid-2008. However, Flume did not file any FBARs until after UBS agreed to turn over its American clients’ records to the IRS. This timing strongly suggested that Flume knew he was breaking the law but continued to believe he could get away with it until it became clear that U.S. authorities would learn of his Swiss account.

- Even if the Court accepted Flume’s claim that he did not know about the FBAR requirement until 2010, his testimony at trial clearly established that he acted with extreme recklessness by failing to review his tax returns before signing them.