Giving A Gift

By Glenn Reyer, CPA

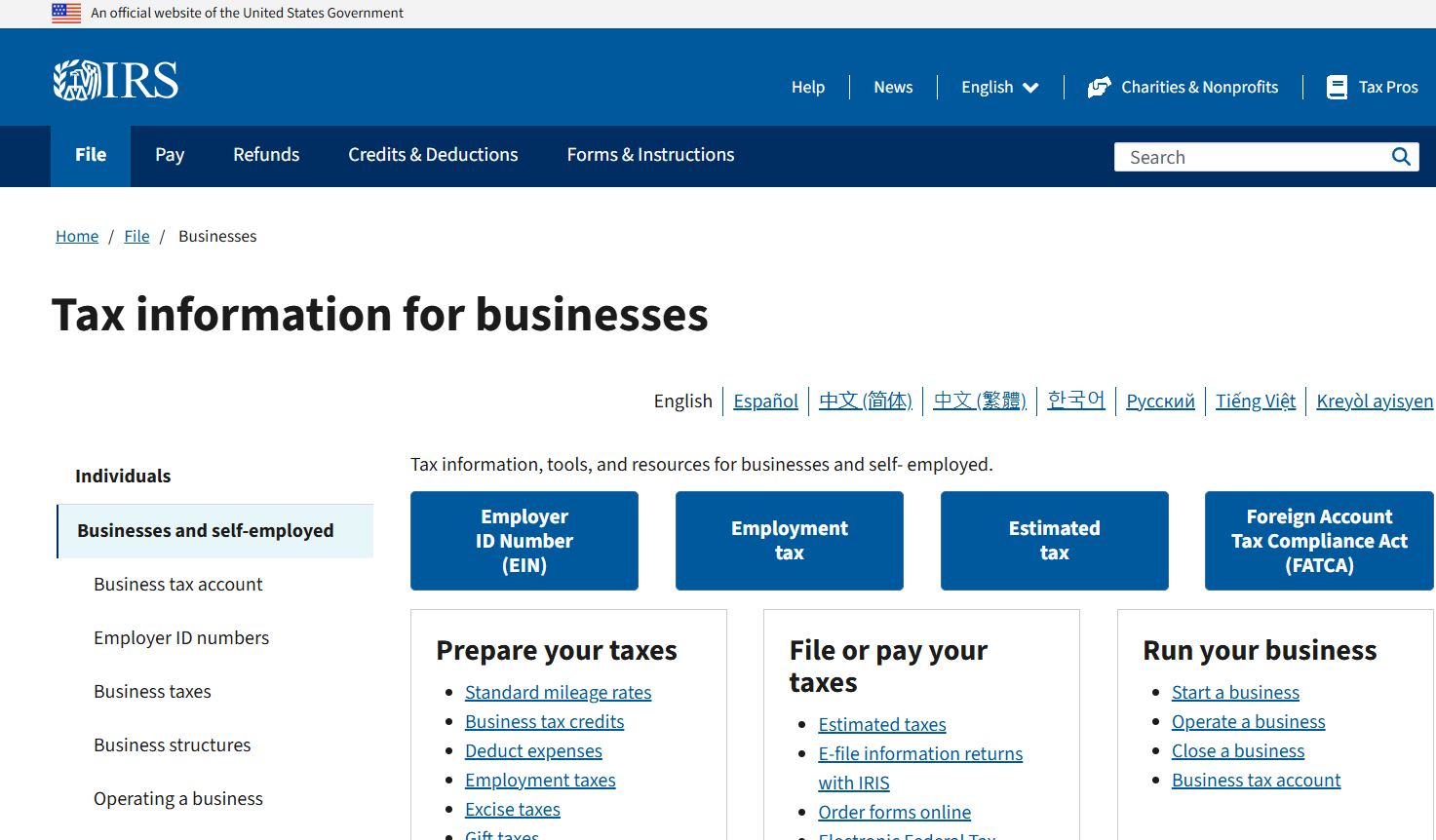

There are many reasons and situations when gifts are given. One thing to remember is, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is interested in the gifts you are giving and how they relate to the gift tax. Unfortunately, there can be tax considerations, in certain situations, when giving a gift. The definition of a gift, according to the IRS, is any transfer to an individual either directly or indirectly, where full consideration measured in money or money’s worth is not received in return. Things that may be considered a gift include cash, property, payments made to a 3rd party on behalf of another, interest free loans, below market sales and many others.

In general, the rule is, any gift is a taxable gift, although there are exceptions to this rule. If the value of the gift is below a certain amount there is no tax consequence related to the gift. This amount is called the annual exclusion. For the annual exclusion to apply, the gift must be of a present interest and not a future interest. A gift of a future interest is somehow limited so that its use, possession or enjoyment will begin at some point in the future. In 2012, the annual exclusion amount allowed for each gift was $13,000. For 2013, the annual exclusion amount is scheduled to increase to $14,000. You can give a gift to anyone. A separate annual exclusion applies to each person to whom you give a gift. Gifting programs, using the annual exclusion amount to keep gifts tax free, are commonly used in estate planning.

In addition to gifts that fall within the annual exclusion amount, there are other non-taxable gifts. Payments made for someone’s education or medical expenses are exempt from federal gift tax. For the educational exclusion, payments must be for tuition only. Books, supplies, room and board do not qualify for the educational exclusion. Payments must be made directly to a qualifying institution. A qualifying institution is a tax-exempt domestic or foreign educational institution. Payments that qualify for the medical exclusion must be made directly to an institution providing medical care to an individual or to a company providing medical insurance to an individual. Qualifying medical expenses are the same as those that are deductible for individual income tax purposes. Due to the unlimited marital deduction, gifts made to a spouse who is a U.S. citizen are exempt from gift tax. If the spouse is not a U.S. citizen there is a special annual exclusion of $139,000 for 2012. The special annual exclusion will increase to $143,000 in 2013. Gifts to a political organization for the organization’s use are excluded from gift tax. Gifts to qualifying charities are not subject to gift tax and can be deductible as charitable contributions.

If you or your spouse give a gift, the gift can be considered as made one-half by you and one-half by your spouse. This practice is called gift splitting, and both of you must agree to split the gift. By doing this you can each take an annual exclusion for your part of the gift. For 2013, gift splitting will allow married couples to gift up to $28,000 to a person without making a taxable gift.

Form 709 is a gift tax return. It is an annual return due no earlier than January1 and no later than April 15 in the year after the gift was given. If you give a gift to anyone, other than your spouse, that exceeds the annual exclusion and it is not considered a tax-free gift you are required to file a gift tax return. In addition, you are required to file a gift tax return if you and your spouse are splitting a gift, you give someone a gift of a future interest or you give your spouse an interest in property that will be ended by some future event. You can request a 6 month extension of time to file your federal gift tax return. Penalties for late filing and late payment can be imposed unless there is reasonable cause for the delay.

After filing a gift tax return, the IRS has 3 years to contest the value of the gift and whether the gift is taxable. This is called the statute of limitations. Often a gift tax return is filed for a non-taxable gift to start the statute of limitations running in order to give a time frame to the ability of the IRS to contest the value of the gift. The value of some gifts, such as money, is easy to agree upon. Others, such as the value of one share of stock in a closely held business, can become the subject of controversy. Business owners will commonly use a gifting program to transfer ownership in their business. When gifting shares of a closely held business, it is recommended to obtain a qualified valuation of the business so as to determine the value of gifts given.

In addition to the annual exclusion, every U.S. citizen is given a lifetime exclusion from paying gift taxes. This is the amount you can gift in your lifetime before owing any gift taxes. Gifts of amounts below the annual exclusion do not count toward using your lifetime exclusion. Even though a gift may be over the annual exclusion amount and considered taxable, no tax is actually due until a person’s lifetime exclusion is used up. A gift tax return is filed to document using one’s lifetime exclusion. No gift tax is actually owed until the total value of all gifts given exceeds the lifetime exclusion. The exclusion has increased dramatically over the last several years from 1 million in 2010 to 5.12 million in 2012. Due to recent legislation, the lifetime exclusion will be 5.25 million for 2013 and the top tax rate will increase from 35% to 40%.

Prior to 2010, an individual could die and not have used their lifetime exclusion, effectively wasting it. Legislation enacted in 2010 changed this. Starting on or after January 1, 2011, the estate of a decedent can elect to transfer the unused exclusion to the decedent’s surviving spouse. The surviving spouse can then apply this amount, along with his or her own lifetime exclusion, to any tax liability arising from subsequent lifetime gifts and transfers at death. A nonresident surviving spouse who is not a U.S. citizen cannot use this unused exclusion amount, except to the extent allowed by treaty with his or her country of citizenship.

A gift can also be subject to the generation skipping transfer tax, unless the amount of the gift is below the annual exclusion amount. This becomes a concern when the donee is 2 or more generations below the donor’s generation. Enacted in 1976, it was created to prevent gifting to younger generations in order to escape estate tax. Many people use a grandchild or a great-grandchild as a skip person. The skip person does not have to be a family member. Any person 37.5 years younger than the person transferring the gift is considered a skip person. Most gifts will escape this tax due to the estate tax credit.

If your gifts add up to more than your lifetime exclusion, gift tax is normally paid by your estate when you die. People often start giving gifts, up to the annual exclusion, to their heirs as they reach old age. This is a smart and legal way to avoid or reduce estate tax when someone dies. If you have questions regarding gifting or estate planning please call and we will be glad to help you.